The servants in Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @ITV and PBS Masterpiece.

Downton Abbey. Gosford Hall. Manor House. Regency House. Each film follows the servants and takes the viewer up and down back stairways, into kitchens and butler’s pantries, and stables and courtyards. But how were the servants’ quarters laid out, and where were they placed in relation to the public and private rooms that the family used? Each house had a different arrangement, to be sure, but patterns did exist.

A narrow corridor leads from the kitchen. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece.

The interior and exterior shots of Downton Abbey were filmed in Highclere Castle,but because the servant kitchens and bedrooms below-stairs no longer existed as they once were, the servant quarters for the mini-series were reconstructed in Ealing Studios in London. The cost of reconstructing these “plain” rooms was relatively affordable. Imagine if one of the elaborate public rooms had to be reconstructed. As script writer Julian Fellowes observed: “The thing about filming in these great houses is that if you were to start from scratch, you simply couldn’t build this and if you did you would have used up all your budget in one room.”

Servant stairs in Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

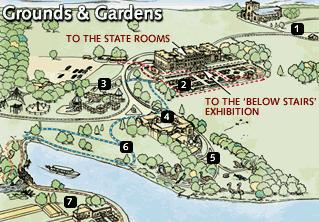

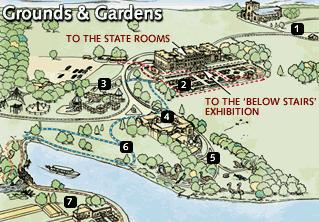

The ground plan from Eastbury Manor House is representative of a great house. It shows the servant quarters at the right near tight round servant stairs, or back stairs, that the servants used instead of the grand staircase reserved for the family and their guests. Maids were expected to work invisibly and sweep and dust when the family was asleep, or work in a room when the family was not scheduled to use it. In fact, many of the lower servants never encountered the family during their years of service.

Unless they were polishing or cleaning the grand staircase, the servants would use the backstairs for all other occasions. A small housemaid’s closet would be located near the back stair on the bedroom floor to accommodate brushes, dusters, pails, and cans. In “modern” Victorian and Edwardian houses, such a closet might contain a sink that provided water for mopping. Some great houses boasted a linen-room on the bedroom floor, where clean bed linen and table linen were stored. In this instance, a dry environment was essential.

Late 19th c. maid and lad at the back entrance

Servants were expected to enter the house in their own entrance, even in smaller houses, such as townhouses. The Regency Townhouse Annex shows a typical entrance below street level. If you click on the links on the various rooms, you can see the other servant areas in this site.

Stairs to servant’s entrance. Bath. Image @Tony Grant

In a country house, the entrance would be in the back of the building or from a courtyard, where supplies could be delivered. The philosophy of a smooth running household was that servants were out of sight and out of mind.

Belowstairs entrance, Bath. Image @Tony Grant

Upon entering, servants would walk along a long hallway to reach the servants’ rooms and other work areas such as the kitchen, scullery, servant’s hall, housekeeper’s room, butler’s room, storage room, etc. Country were at least two or three stories tall. Servants climbed the stairs and came down them again all day long, cleaning, hauling water, carrying meals or coal for fires, and a myriad other duties. They rose before the family, often from top floor garrets with small windows, and worked long after their employers had gone to bed.

Interior, Upstairs Downstairs web page. Notice the tiny garret bedrooms.

In this image, you can see the small garret rooms reserved for servants in the attic of a townhouse. Men’s and women’s quarters were separated, as in Downton Abbey, with the women’s quarters called the virgin’s wing. The most common servant quarters are described below.

A meal belowstairs. Downton Abbey. Notice the servant bells on the back wall. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

Servant’s Hall:

The servant’s hall was a common room where the work staff congregated, ate their meals, performed small but essential tasks, like mending, darning, polishing, ect. A long table was its main feature, as well as a window that would let in enough light for the tasks that needed to be accomplished. This window is a feature in images of several servants halls, which makes me think it was essential, for many of their tasks (darning, polishing shoes, ironing, and the like) required good light.

1907 Watercolor of the windows in a servant’s hall

The servants would regard the hall as their living room, for they ate their meals there and congregated in the hall for the evening. Often the cook did not regard making the servants’ meals as part of her duty, and this task would be left to the kitchen maids. Servants would also receive the visitors’ servants here (as in Gosford Park), persons of similar rank, or their own visitors on a very rare occasion.

Image of Victorian servants eating dinner in the servants hall.

The servant bells were located in this area, as well as hooks for coats and uniforms.

Daisy puts on her coat as William speaks to her just outside the servants hall. Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS masterpiece

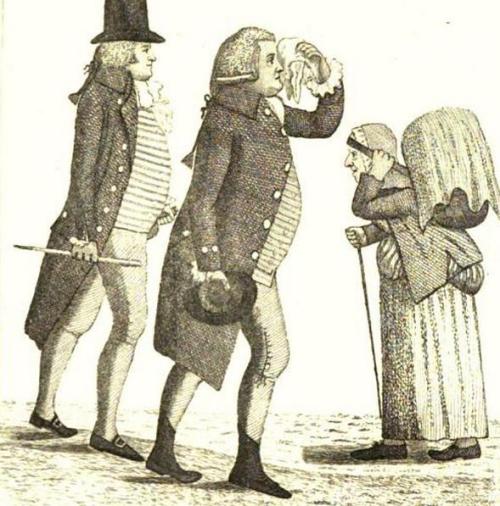

The servants followed a hierarchy downstairs as strict as upstairs, and the upper servants, the butler, housekeeper, cook, valet and ladies maid would be served meals and tea by the lower servants. The highest ranking servant was the stewart, then came the butler and housekeeper.

Anna completes a task in the servants hall. Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

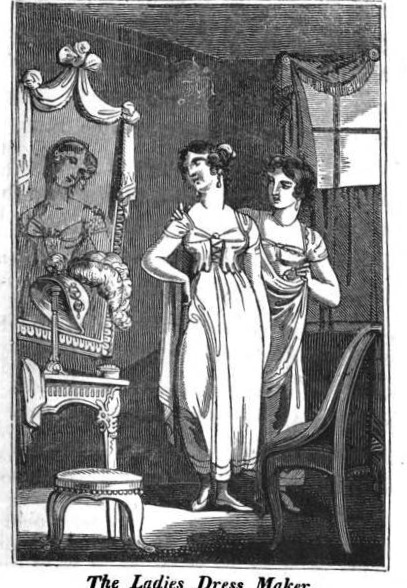

The ladies maid would defer to the housekeeper and the valet to the butler. Standing low down was the scullery maid or tweeny, who often was just a young girl of twelve or thirteen. Her hours were the longest, for she would make sure that the water was boiling for the cook before she began her day.

Kitchen:

The long work table is the focal point of the kitchen. Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

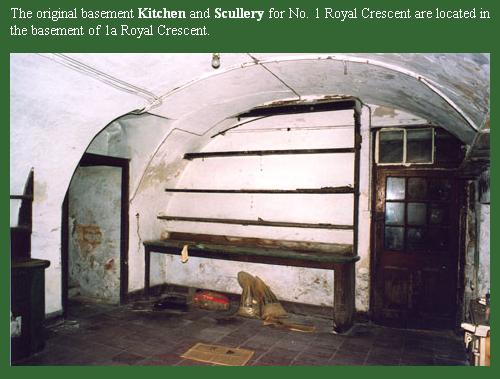

The kitchen even in great houses were utilitarian, and positioned away from the family quarters to keep cooking smells away yet near enough for the delivery of food. Kitchens were also located near an entrance were supplies could be delivered, and near the kitchen gardens (but not always. See below.)

Harewood house and grounds. The kitchen was a 20-minute walk to the walled garden.

Kitchens tended to be oblong and dominated by a large kitchen table, where the majority of food preparation was done. The window would be ideally positioned to the left side of the range, and the kitchen dresser, where essential equipment was held, would stand close to the work table.

Kitchen suite, 1900 house.

The cook worked under the housekeeper, but the kitchen was her domain. She saw to its cleanliness and neatness, and made sure the larders were well-stocked. Not only were the floors, shelves, and work spaces scrubbed, but they had to be thoroughly dried to prevent mold and mildew from contaminating food stuffs and work tops. The arrangement of the scullery and kitchen was convenient, so that one did not need to cross the kitchen to reach the scullery. Natural light in both rooms needed to be ample.

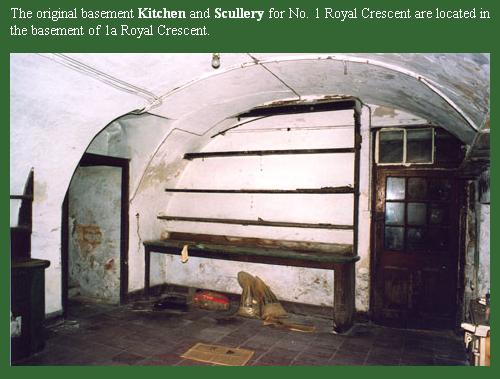

This kitchen in the Royal Crescent in Bath needs renovation and preservation.

She (for by the end of the 19th century, most of the cooks in British households were female) oversaw the meals and kitchen staff, consisting of kitchen maids and the scullery maid.

Scullery and kitchen in the Fota House, Ireland

Scullery:

Cleaning in the scullery

The scullery was always located in a separate room from the kitchen so that food would not be contaminated by soiled water. Double stone sinks were the main feature of this room, where pots and pans and the servants’ crockery were rinsed and cleaned. The family’s fine china would be washed in a copper sink, whose softer surface prevented chipping. A cistern above the sinks was used to flush the drains, which led out of house. This was one reason that sculleries were located next to the outer walls and nearest the courtyards or an outer garden. Often, the scullery had no door into the kitchen (only a pass through), and one could enter the room only from the outside. An outside door in the scullery was also known as the “tradesmen’s entrance”.

Scullery, Image @Harewood House.

Food preparation also occurred in this area, such as chopping vegetables. Hygiene was essential in order not to contaminate existing food supplies, or the people within the house with soiled cutlery or water. This meant constant hauling of fresh water, scrubbing, washing, and cleaning. The scullery floor, made of stone, was lower than the kitchen’s, which prevented water from flowing into the cooking areas. Dry goods were stashed well away from the scullery, which also had to be kept dry in order to prevent mold. To prevent standing in water all day long, raised latticed wood mats were placed by the sink for the scullery maid to stand upon.

Panorama of a Victorian scullery with boiler and laundry features

Sculleries also contained a copper for boiling clothes on laundry day, washtubs, washboards, irons, and cabinets for cleaning supplies. In 1908, an eight-room house required 27 hours per week of labor, which did not include laundering clothes. One can only imagine how long a house the size of Downton Abbey took to manage.

Scullery sinks, Chawton

She stood at a sink behind a wooden dresser backed with choppers and stained with blood and grease, upon which were piles of coppers and saucepans that she had to scour, piles of dirty dishes she had to wash. Her frock, her cap, her face and arms were more or less wet, soiled, perspiring and her apron was a filthy piece of sacking, wet and tied round her with a cord. The den where she wrought was low, damp, ill-smelling, windowless, lighted by a flaring gas-jet……with many ugly dirty implements around her. – The History of Country House Staff

In this 17th c. image, the scullery maid stands upon a platform to keep her feet dry.

In Downton Abbey, the scullery maid is nowhere to be seen. (Daisy is the kitchen maid, with vastly different duties.) Two modern women who played the scullery maid in Manor House quit the series, unable to pursue that role for the duration of the series. Only the third person, Ellen Beard, who had a better understanding of the scullery maid’s duties of endless washing, managed to remain at her station until the very end. Click on this link to hear a short podcast of a Scottish scullery maid, who described her job as slave labor.

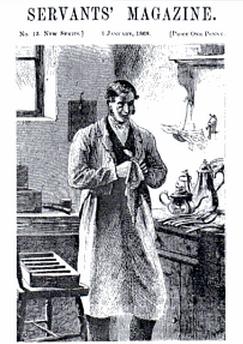

The butler polishes the silver, 1868.

Butler’s room and Butler’s Pantry

The duties of the butler confine him to the drawing-room and dining-room. The dining-room, however, is his particular domain; he sees that everything is in order, that the table is laid correctly, the lighting effect satisfactory, the flowers arranged, and in short that the room and appointments are in perfect readiness for a punctual meal. In this work a parlor maid assists him by sweeping and dusting, and a pantry-maid helps him by keeping everything immaculate and in readiness in the pantry. The butler serves at breakfast, luncheon and dinner.” – Vintage Maids and Butlers

Butlert’s pantry, 1896. Staatsburg House, McKim, Mead, & White

The butler’s rooms, which included the Butler’s Pantry, were located in the basement nearest the dining room upstairs and back entry, and had no connection with the kitchen, except for service. When he was summoned, even in his rooms, the butler could appear quickly. In smaller establishments, such as Matthew Crawley’s house, the butler also acted as valet. In all instances, except for the steward, he was the highest-ranking servant, answering directly to the master.

One of the duties of the butler (Mr. Carson in Downton Abbey) is to account for the wine. In this instance, he notices a discrepancy in the tally and the books. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

The butler’s pantry was kept under lock and key, so that thievery was impossible at best, and at the very least deterred. A plate-closet or safe were placed there, as well as a private scullery for cleaning. The butler’s bedroom was a necessary (and lockable) adjunct in large houses for the protection of the plate.

Mrs. Hughes and Mr. Carson chat in her sitting room. Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

The Housekeeper’s Room

The housekeepers room in large establishments served as both a sitting- and business-room where she would take the directions of the day from the lady of the house. She would also entertain visitors of similar rank in her quarters. The housekeeper oversaw the female servants, and when she walked, a thick assortment of keys, symbols of her status and which dangled from her waist, would jiggle and certainly make a sound.

The housekeeper’s room in Uppark. At times the upper servants would congregate there for tea, and in some houses, for dinner.

Before dinner in the servants hall, the upper servants would assemble in the housekeeper’s room, also known as the Pug’s Parlour, and walk in for dinner, with the butler leading the way. This was known as the Pug’s Parade. After dinner, the upper servants would withdraw to the housekeeper’s parlor again for conversation.

Servant Bedrooms

Anna and Gwen confronted by O’Brien in their unlocked room. Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

In the latter half of the 19th century, servants slept in attic bedrooms. These were often cold and damp in the winter and hot in the summer, with little light coming in from small windows. Some male servants slept downstairs to guard the family silver. The furnishings in servant quarters were basic and essential. A servant might have a locked box in which personal materials were kept, but the rooms were open and subject to inspection by their employers.

The valet’s simple bedroom. Downton Abbey. Image courtesy @PBS Masterpiece

One source for servant quarters and duties of the servants cautioned that books about servant etiquette discussed ideal behavior. In reality, servant turnover was high, theft did occur, and servants did not always know their place. In this humorous Punch cartoon, the mistress arrived home unexpectedly, catching the servants eating upstairs and generally misbehaving. The truth, I suspect, is somewhere in between.

“Oh, hey, the missus! Servants eating a meal upstairs.” Cruikshank. Punch

Sources: (A long list that fleshes out the topic.)

Read Full Post »