As we enjoy the crisp air of autumn, let’s take a tour of October in Jane Austen’s World! We’ll look at her life and times through the lens of her letters, novels, and personal interests and see what we can learn about Regency life in the month of October.

If you’re just jumping on the bus, you can find previous articles in the “A Year in Jane Austen’s World” series here: January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, and September.

First off, let’s see what Jane Austen’s beautiful Hampshire countryside looks like in October. Big changes occur as the month continues, which means the lush green of summer turns to the yellow, gold, and ruby colors of fall. Here is a stunning photo of Chawton House Gardens:

October in Hampshire

October in Jane Austen’s Hampshire brings a total change of atmosphere. The leaves turn, and the weather cools and crisps, just like the apples in the orchard at Chawton House. As is our tradition, I’ve collected a few snippets from Austen’s letters regarding the season change, weather, and gardens/orchards:

24 October 1798 (“Bull & George,” Dartford): “My day’s journey has been pleasanter in every respect than I expected. I have been very little crowded and by no means unhappy. Your watchfulness with regard to the weather on our accounts was very kind and very effectual. We had one heavy shower on leaving Sittingbourne, but afterwards the clouds cleared away, and we had a very bright chrystal afternoon.”

27 October 1798 (Steventon): “I understand that there are some grapes left, but I believe not many; they must be gathered as soon as possible, or this rain will entirely rot them.”

24 October 1808 (Castle Square): “We have just had two hampers of apples from Kintbury, and the floor of our little garret is almost covered.”

11 October 1813 (Godmersham Park): “We had thunder and lightning here on Thursday morning, between five and seven; no very bad thunder, but a great deal of lightning. It has given the commencement of a season of wind and rain, and perhaps for the next six weeks we shall not have two dry days together.”

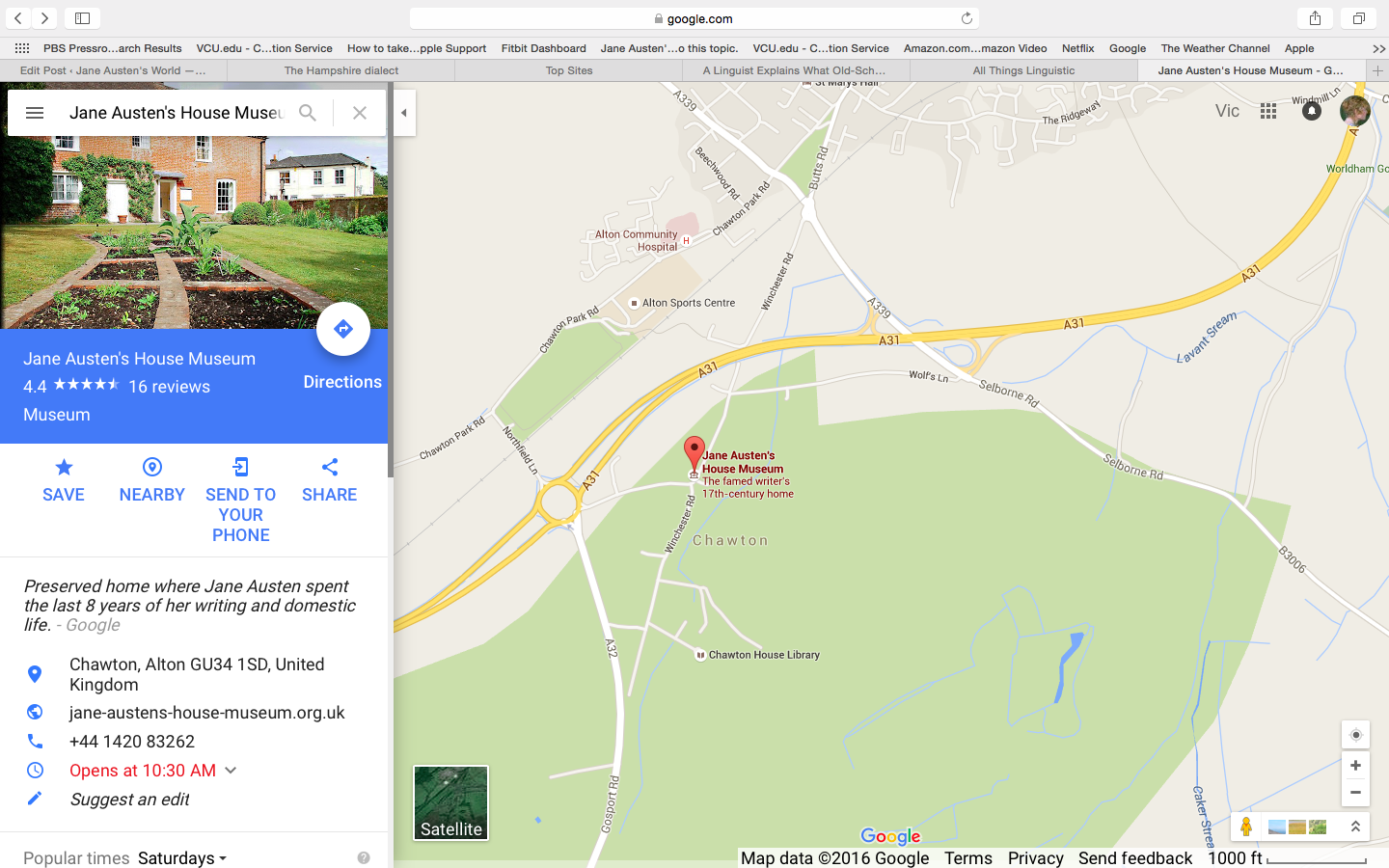

Such detailed descriptions of October! Here now is a current glimpse of Jane Austen’s House Museum and its gardens in October:

October in Jane Austen’s Letters: Jane’s Writing

While there are other October letters to consider, there is one excerpt that requires our attention first because it pertains to the safekeeping of Austen’s writing!

24 October 1798 (“Bull and George,” Dartford):

- “I should have begun my letter soon after our arrival, but for a little adventure which prevented me. After we had been here a quarter of an hour it was discovered that my writing and dressing boxes had been by accident put into a chaise which was just packing off as we came in, and were driven away toward Gravesend in their way to the West Indies. No part of my property could have been such a prize before, for in my writing-box was all my worldly wealth, 7l., and my dear Harry’s deputation. Mr. Nottley immediately despatched a man and horse after the chaise, and in half an hour’s time I had the pleasure of being as rich as ever; they were got about two or three miles off.”

Thank goodness her writing box was found (and any money stowed in it). And what a beautiful description: “all my worldly wealth.” Though money and paperwork are important, one wonders if any of her writing might also have been in that box–a letter, a scene, a phrase. That would be treasure indeed.

October in Jane Austen’s Letters: A Great Loss

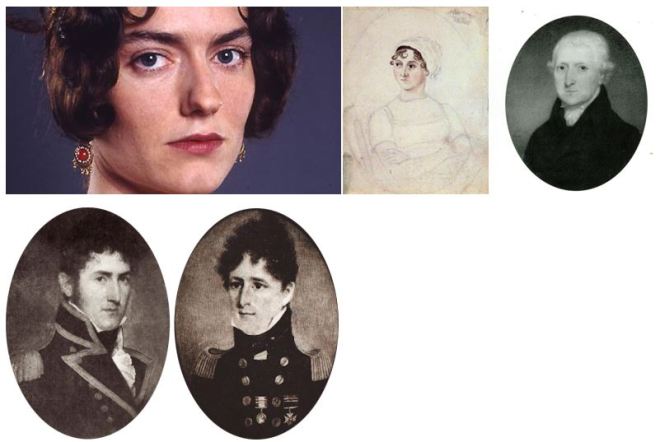

Now we must turn our main focus to Austen’s letters dating from October 1808. For those of us who take a personal interest in Jane Austen’s life and family, this is the month when Elizabeth Austen, Edward’s darling wife, died (10 October 1808).

Elizabeth Austen nee Bridges (1773-1808) married Edward Austen (Knight) on 27 December 1791, in Goodnestone, Kent, England. They had a large family and were very happily married. She was 35 when she passed and Edward never remarried.

The letters between Jane and Cassandra during that time are particularly tender. Both sisters mourned her death, but as is usual when a family member loses a spouse, they were even more concerned for Edward and his children (Jane’s nieces and nephews). I highly recommend reading the letters in full on your own, but below are several excerpts that share the beautiful manner in which Jane and Cassandra helped to comfort Edward and his children as they grieved the lost of a beloved wife and mother:

13 October (Castle Square):

- First news of Elizabeth’s death: “My dearest Cassandra,—I have received your letter, and with most melancholy anxiety was it expected, for the sad news reached us last night, but without any particulars. It came in a short letter to Martha from her sister, begun at Steventon and finished in Winchester.”

- Family Condolences: “We have felt, we do feel, for you all, as you will not need to be told,—for you, for Fanny, for Henry, for Lady Bridges, and for dearest Edward, whose loss and whose sufferings seem to make those of every other person nothing. God be praised that you can say what you do of him: that he has a religious mind to bear him up, and a disposition that will gradually lead him to comfort.”

- Fanny Knight: “My dear, dear Fanny, I am so thankful that she has you with her! You will be everything to her; you will give her all the consolation that human aid can give. May the Almighty sustain you all, and keep you, my dearest Cassandra, well; but for the present I dare say you are equal to everything.”

- Update on the boys: “You will know that the poor boys are at Steventon. Perhaps it is best for them, as they will have more means of exercise and amusement there than they could have with us, but I own myself disappointed by the arrangement. I should have loved to have them with me at such a time. I shall write to Edward by this post.”

15 October (Castle Square):

- Concern for Edward: “Your accounts make us as comfortable as we can expect to be at such a time. Edward’s loss is terrible, and must be felt as such, and these are too early days indeed to think of moderation in grief, either in him or his afflicted daughter, but soon we may hope that our dear Fanny’s sense of duty to that beloved father will rouse her to exertion. For his sake, and as the most acceptable proof of love to the spirit of her departed mother, she will try to be tranquil and resigned. Does she feel you to be a comfort to her, or is she too much overpowered for anything but solitude?”

- Concern for Lizzy: “Your account of Lizzy is very interesting. Poor child! One must hope the impression will be strong, and yet one’s heart aches for a dejected mind of eight years old.”

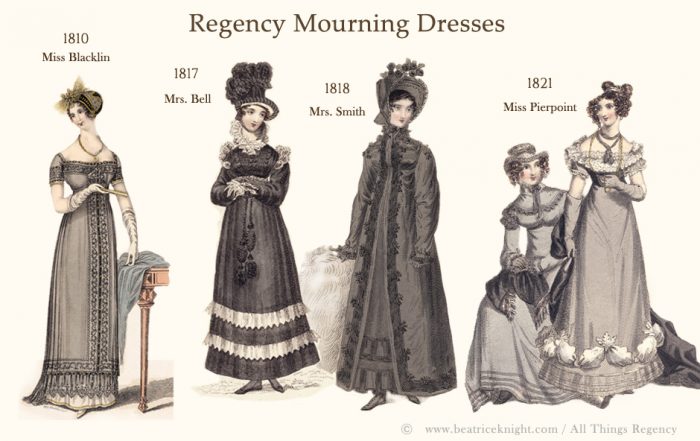

- Mourning clothes for Cassandra: “Your parcel shall set off on Monday, and I hope the shoes will fit; Martha and I both tried them on. I shall send you such of your mourning as I think most likely to be useful, reserving for myself your stockings and half the velvet, in which selfish arrangement I know I am doing what you wish.

- Mourning clothes for Jane: “I am to be in bombazeen and crape, according to what we are told is universal here, and which agrees with Martha’s previous observation. My mourning, however, will not impoverish me, for by having my velvet pelisse fresh lined and made up, I am sure I shall have no occasion this winter for anything new of that sort. I take my cloak for the lining, and shall send yours on the chance of its doing something of the same for you, though I believe your pelisse is in better repair than mine. One Miss Baker makes my gown and the other my bonnet, which is to be silk covered with crape.”

- Sisterly Condolences: “That you are forever in our thoughts you will not doubt. I see your mournful party in my mind’s eye under every varying circumstance of the day; and in the evening especially figure to myself its sad gloom: the efforts to talk, the frequent summons to melancholy orders and cares, and poor Edward, restless in misery, going from one room to another, and perhaps not seldom upstairs, to see all that remains of his Elizabeth. Dearest Fanny must now look upon herself as his prime source of comfort, his dearest friend; as the being who is gradually to supply to him, to the extent that is possible, what he has lost. This consideration will elevate and cheer her. Adieu. You cannot write too often, as I said before. We are heartily rejoiced that the poor baby gives you no particular anxiety. Kiss dear Lizzy for us. Tell Fanny that I shall write in a day or two to Miss Sharpe.”

24 October (Castle Square):

- Edward’s sons arrive: “Edward and George came to us soon after seven on Saturday, very well, but very cold, having by choice travelled on the outside, and with no greatcoat but what Mr. Wise, the coachman, good-naturedly spared them of his, as they sat by his side. They were so much chilled when they arrived, that I was afraid they must have taken cold; but it does not seem at all the case: I never saw them looking better.”

- Jane’s Affectionate Observations: “They behave extremely well in every respect, showing quite as much feeling as one wishes to see, and on every occasion speaking of their father with the liveliest affection. His letter was read over by each of them yesterday, and with many tears; George sobbed aloud, Edward’s tears do not flow so easily; but as far as I can judge they are both very properly impressed by what has happened. Miss Lloyd, who is a more impartial judge than I can be, is exceedingly pleased with them.”

- Entertaining the boys: “George is almost a new acquaintance to me, and I find him in a different way as engaging as Edward. We do not want amusement: bilbocatch, at which George is indefatigable, spillikins, paper ships, riddles, conundrums, and cards, with watching the flow and ebb of the river, and now and then a stroll out, keep us well employed; and we mean to avail ourselves of our kind papa’s consideration, by not returning to Winchester till quite the evening of Wednesday.”

- Church on Sunday: “I hope your sorrowing party were at church yesterday, and have no longer that to dread. Martha was kept at home by a cold, but I went with my two nephews, and I saw Edward was much affected by the sermon, which, indeed, I could have supposed purposely addressed to the afflicted, if the text had not naturally come in the course of Dr. Mant’s observations on the Litany: ‘All that are in danger, necessity, or tribulation,’ was the subject of it.”

- Sunday walk: “The weather did not allow us afterwards to get farther than the quay, where George was very happy as long as we could stay, flying about from one side to the other, and skipping on board a collier immediately.”

- Sunday evening: “In the evening we had the Psalms and Lessons, and a sermon at home, to which they were very attentive; but you will not expect to hear that they did not return to conundrums the moment it was over… While I write now, George is most industriously making and naming paper ships, at which he afterwards shoots with horse-chestnuts, brought from Steventon on purpose; and Edward equally intent over the ‘Lake of Killarney,’ twisting himself about in one of our great chairs.”

25 October (Castle Square) – contained in the same post:

- Updates on Edward: “All that you say of Edward is truly comfortable; I began to fear that when the bustle of the first week was over, his spirits might for a time be more depressed; and perhaps one must still expect something of the kind.”

- Adventures to Northam and Hopeful Plans for Netley: “We had a little water-party yesterday; I and my two nephews went from the Itchen Ferry up to Northam, where we landed, looked into the 74, and walked home, and it was so much enjoyed that I had intended to take them to Netley to-day; the tide is just right for our going immediately after moonshine, but I am afraid there will be rain; if we cannot get so far, however, we may perhaps go round from the ferry to the quay. I had not proposed doing more than cross the Itchen yesterday, but it proved so pleasant, and so much to the satisfaction of all, that when we reached the middle of the stream we agreed to be rowed up the river; both the boys rowed great part of the way, and their questions and remarks, as well as their enjoyment, were very amusing; George’s inquiries were endless, and his eagerness in everything reminds me often of his uncle Henry.”

- Evening Entertainment: “Our evening was equally agreeable in its way: I introduced speculation, and it was so much approved that we hardly knew how to leave off.”

October in Jane Austen’s Novels

Sense and Sensibility

- Private Balls and Parties: “When Marianne was recovered, the schemes of amusement at home and abroad, which Sir John had been previously forming, were put into execution. The private balls at the park then began; and parties on the water were made and accomplished as often as a showery October would allow.”

- Colonel Brandon’s Fateful Letter: “The first news that reached me of her [little Eliza] came in a letter from herself, last October. It was forwarded to me from Delaford, and I received it on the very morning of our intended party to Whitwell; and this was the reason of my leaving Barton so suddenly, which I am sure must at the time have appeared strange to every body, and which I believe gave offence to some. Little did Mr. Willoughby imagine, I suppose, when his looks censured me for incivility in breaking up the party, that I was called away to the relief of one whom he had made poor and miserable; but had he known it, what would it have availed? Would he have been less gay or less happy in the smiles of your sister? No, he had already done that, which no man who can feel for another would do. He had left the girl whose youth and innocence he had seduced, in a situation of the utmost distress, with no creditable home, no help, no friends, ignorant of his address! He had left her, promising to return; he neither returned, nor wrote, nor relieved her.”

Pride and Prejudice

- Mr. Collins Writes to Mr. Bennet: Excerpts from letter, from “Hunsford, near Westerham, Kent, 15th October,” read as follows:

“The disagreement subsisting between yourself and my late honoured father always gave me much uneasiness; and, since I have had the misfortune to lose him, I have frequently wished to heal the breach: but, for some time, I was kept back by my own doubts, fearing lest it might seem disrespectful to his memory for me to be on good terms with anyone with whom it had always pleased him to be at variance… As a clergyman, moreover, I feel it my duty to promote and establish the blessing of peace in all families within the reach of my influence…

“If you should have no objection to receive me into your house, I propose myself the satisfaction of waiting on you and your family, Monday, November 18th, by four o’clock, and shall probably trespass on your hospitality till the Saturday se’nnight following, which I can do without any inconvenience, as Lady Catherine is far from objecting to my occasional absence on a Sunday, provided that some other clergyman is engaged to do the duty of the day.”

Mansfield Park

- Tom Bertram on Hunting: “We have just been trying, by way of doing something, and amusing my mother, just within the last week, to get up a few scenes, a mere trifle. We have had such incessant rains almost since October began, that we have been nearly confined to the house for days together. I have hardly taken out a gun since the 3rd. Tolerable sport the first three days, but there has been no attempting anything since.”

- Mr. Crawford on Fanny: “You see her every day, and therefore do not notice it; but I assure you she is quite a different creature from what she was in the autumn. She was then merely a quiet, modest, not plain-looking girl, but she is now absolutely pretty. I used to think she had neither complexion nor countenance; but in that soft skin of hers, so frequently tinged with a blush as it was yesterday, there is decided beauty; and from what I observed of her eyes and mouth, I do not despair of their being capable of expression enough when she has anything to express. And then, her air, her manner, her tout ensemble, is so indescribably improved! She must be grown two inches, at least, since October.”

- Miss Crawford’s Response: “Phoo! phoo! This is only because there were no tall women to compare her with, and because she has got a new gown, and you never saw her so well dressed before. She is just what she was in October, believe me. The truth is, that she was the only girl in company for you to notice, and you must have a somebody.”

Emma

- Emma Longs for Isabella’s Christmas Visit: “[Emma’s] sister, though comparatively but little removed by matrimony, being settled in London, only sixteen miles off, was much beyond her daily reach; and many a long October and November evening must be struggled through at Hartfield, before Christmas brought the next visit from Isabella and her husband, and their little children, to fill the house, and give her pleasant society again.”

- Mrs. Weston on Mr. Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax: “‘You may well be amazed,’ returned Mrs. Weston, still averting her eyes, and talking on with eagerness, that Emma might have time to recover— ‘You may well be amazed. But it is even so. There has been a solemn engagement between them ever since October—formed at Weymouth, and kept a secret from every body. Not a creature knowing it but themselves—neither the Campbells, nor her family, nor his.—It is so wonderful, that though perfectly convinced of the fact, it is yet almost incredible to myself. I can hardly believe it.—I thought I knew him.'”

- Mr. and Mrs. Weston’s Pain: “Engaged since October,—secretly engaged.—It has hurt me, Emma, very much. It has hurt his father equally. Some part of his conduct we cannot excuse.”

- Emma and Mr. Knightley get married in October:

- “Before the end of September, Emma attended Harriet to church, and saw her hand bestowed on Robert Martin…”

- “The Mr. Churchills were also in town; and they were only waiting for November. The intermediate month was the one fixed on, as far as they dared, by Emma and Mr. Knightley. They had determined that their marriage ought to be concluded while John and Isabella were still at Hartfield, to allow them the fortnight’s absence in a tour to the seaside, which was the plan.”

- “But Mr. John Knightley must be in London again by the end of the first week in November.”

- “[Emma] was able to fix her wedding-day—and Mr. Elton was called on, within a month from the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Martin, to join the hands of Mr. Knightley and Miss Woodhouse.”

October Dates of Importance

This brings us now to several important October dates relating to Jane and her family:

Family News:

7 October 1767: Edward Austen born at Deane.

25 October 1804: Austen family returns to Bath and lives at 3 Green Park Buildings East.

October 1806: Austen women move to Southampton to live with Francis Austen and wife Mary.

14 October 1812: Edward Austen officially adopts “Knight” as surname.

4 October 1815: Austen travels to London and stays two months to nurse Henry during his illness.

Historic Dates:

19 October 1781: Major British defeat at the Battle of Yorktown, marking the end of the fighting during the American Revolutionary War.

16 October 1793: Marie Antoinette executed in France.

1 October 1801: Truce between Britain and France.

21 October 1805: Nelson defeats French-Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Writing:

October 1796: Austen begins writing “First Impressions” (later revised as Pride and Prejudice).

30 October 1811: Sense and Sensibility published “By a Lady.”

Sorrows:

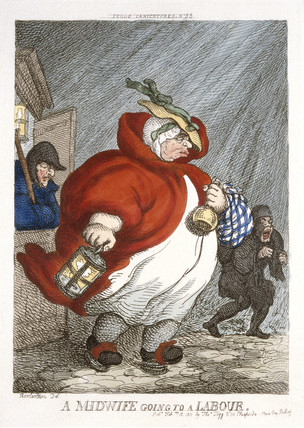

10 October 1808: Elizabeth Austen (Edward’s wife) dies after eleventh childbirth.

October

As we round the corner into the last few months of the year, it’s fascinating to find so many interesting tidbits each month in Jane Austen’s letters, novels, and life. Next month, we’ll take a look at November in Jane Austen’s World!

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Now Available: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.