Curious readers: Tony Grant (London Calling) has contributed an article about Kew Gardens and his beautiful photographs to go with it. Relax and enjoy this visual feast of gardens, walkways, and flowers.

I have been to Kew Gardens, which is only a couple of miles from where I live, on the other side of Richmond upon Thames, many, many times for more than thirty years. When I first visited Kew gardens all those years ago the charge to get through those regal, ornate gates was 1p, a penny, a mere token payment. Kew is a government research centre and a leading authority on plants throughout the world. I think they felt in those far off days that a token payment, just to keep the paths swept, was all that was required. It was and is a government-owned establishment, and so by default, we, the British public, own it, (A little like The National Gallery and The National Portrait Gallery. Those paintings belong to me you know. So, why shouldn’t I get in free?)

Nowadays, it costs an arm and a leg to get into Kew Gardens. I’ll whisper this; “it’s £13.90 for an adult.” The Government decided, to help finance research, and to develop further public facilities in the gardens, we should all pay to get in. It’s such a beautiful place and such an elemental place that, yes, I’ll pay to get in. No questions asked. I need my dose of Kew. And many, many thousands of others just love to pay to get in too.

Oh, by the way, if you are a mum with a baby and young toddlers in tow, it’s free for the children, totally free. An example of British quirkiness in action. The gardens are a great place to meet for morning coffee in one of the 18th-century orangeries, to have a chat and a place to let the youngsters roam.

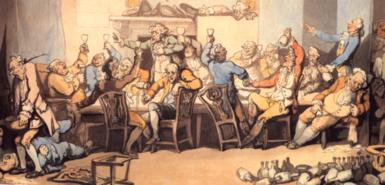

My first encounter with Kew, I must admit, involved fellow students, bottles of wine, cans of beer, some very attractive females (my future wife amongst them), and an appreciation of nature and trees gained by lying on my back looking up through leafy branches to a clear blue sunny sky beyond.

Kew to me means pleasant tree-lined walks, elegant plant houses with their acres of glass and miles of fine wrought iron structural parts painted white and curved and curled into shapely structures. It is a place to look closely at beautiful flowers, contemplating their wondrous shapes and form, and their intense colours, and to take in their seductive perfumes. It is uplifting to observe the majesty of the many varieties of trees, with their beautiful patterned leaves, and their branch and twig systems like fine black lace against changing skies.

Kew calms the spirit. It is a meditative place. You can become one with yourself as you walk around or find a place on the grass to sit.

It is vast enough to give you personal space and there is tranquillity amongst the greens and shade.

The Importance of Kew

Kew is an important place. It has a seed bank that holds 10% of all the worlds’ plant species, and contains samples of nearly all endangered species. It also has a herbarium whose collection is being added to virtually daily. At the Joderell Laboratory at Kew, they research the molecular systems, and study the physiology and biochemistry of plants. They study the plants to find natural medicines, specifically for anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory drugs. One department focuses on agricultural research, and there are also botanical illustration and photography departments. Kew is a world leader in conservation and plant technology.

Development of Kew

The development of Kew began in the 16th century when Henry VII built a palace at Richmond just along the Thames from Kew. By the 17th century the area round Richmond had become established as a hub of political power for part of the year. Everybody who was part of the court and the government came there in the summer when the king was in residence. Later, James I combined all the royal land in the area, along with former monastic land, with the park that existed at Shene, and created a new hunting ground of 370 acres. Robert Stickles, the architect, built a hunting lodge called Richmond Lodge right in the middle of it.

After Charles I was executed, and The Commonwealth had taken over under Oliver Cromwell, much of the Royal property around Richmond and Kew was sold off. However, those sales were reversed during the reign of William III. Robert Stickles’s Richmond Lodge had survived, and it was extended and turned into a royal palace. The old deer park was reassembled, and the land around Richmond Lodge was turned into formal gardens. So began what we know today as Kew Gardens.

In the 1690’s, George London created the Broad Avenue, a wide path that goes nearly the full length of the gardens connecting many of the main gardens features. Charles Bridgeman and William Kent, two great 18th century landscape gardeners, primarily created the layout and design of the original gardens.

Capability Brown added to the design later. Because of these three great garden designers’ influences and ideas, the garden at Kew were watched and visited, so that new ideas in garden design could be disseminated. Kew was an important influence to 18th century garden design throughout Britain.

This early 18th-century plan was overlaid by later designers, although some of the Capability Brown’s features still persist. It is also likely that some of the older trees might have been planted by Charles Bridgeman. In 1731, King George II’s son, Frederick, Prince of Wale,s leased Kew farm. In 1736 he married Princess Augusta of Saxe Gotha, and together they began some drastic changes at Kew. They commissioned William Kent to redesign Richmond Lodge. He added extensions and covered the façade in white stucco. It became known as The White House.

Frederick and Augusta were garden enthusiasts, and they were helped by the Earl of Bute, who advised them on obtaining plants and landscaping. He later became the tutor to their son, who became George III. Unfortunately, Frederick died in 1751 due to a bout of pleurisy and a burst abscess in his chest. He wasn’t able to fulfil his plans for the gardens. At the time it was said his death was a great loss to the development of gardening in this country. George III, Frederick’s son, succeeded to the throne on the death of his grandfather, George II in 1760.

Capability Brown was commissioned to re-landscape the gardens. The royal family used Richmond Lodge as a summer home. When, Princess Augusta, George’s wife, died, the royal family moved to the White House, whilst The prince of Wales and his brother Prince Frederick lived in the Dutch House, which still exists today and is now called Kew Palace. The royal children were given lessons in botany and botanical illustration. During his bouts of illness, the King lived at Kew.

During the Georgian period Joseph Banks became friends with George III and was the unofficial director of Kew Gardens. He became one of the most influential botanists of his time and began many of the work botanists do today.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743 – 1820)

In 1761he inherited his father’s estate in Lincolnshire to which was attached considerable wealth. His first voyage of discovery was to the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador on the ship HMS Niger. On his return to London in 1767 he was elected a member of the Royal Society at the tender age of 23.

When the society proposed an expedition to observe the transit of Venus in the Pacific in 1769, Joseph Banks financed his own expedition with his own team of scientists, including the botanist Daniel Solander and the artist Sydney Parkinson. HMS Endeavor under Captain Cook left England in August 1768.

Joseph Banks’ botanical collection formed the basis of the Herbarium at Kew today. His original specimens an still be studied there. Later he mounted expeditions to Iceland, the Hebrides, and the Orkneys. Banks helped organise the first collections at Kew. Specimens arrived from all over the growing British Empire, a typical trait with Empire building.

The initial impulse were trade and wealth, but so many other things went along in parallel with that: science, exploration, discovery, art, culture. The British Empire brought religion, government, and even citizenship along with it. You can see examples and parallels with The Roman Empire, the Spanish exploration of South America, and present-day empire building.

Kew is a special place, and a visit there brings home the importance of plants, the keystone of our planet and very existence. They do so much for us, and their beauty brings us peace and joy. Is it such a strange thing to do – hug a tree?

More images: