Thomas Lawrence Exhibit, National Portrait Gallery, London. Image @Tony Grant

Gentle readers, if you are lucky enough to be near London you have only a few days to see the exhibit at the National Portait Gallery of the splendid painter, Thomas Lawrence. This is Tony Grant’s (London Calling) review of the show.

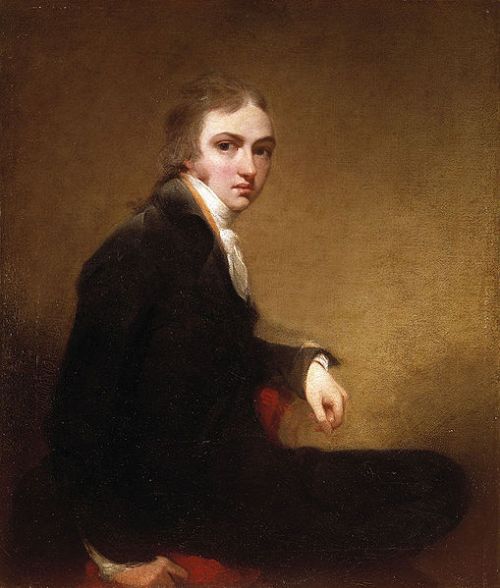

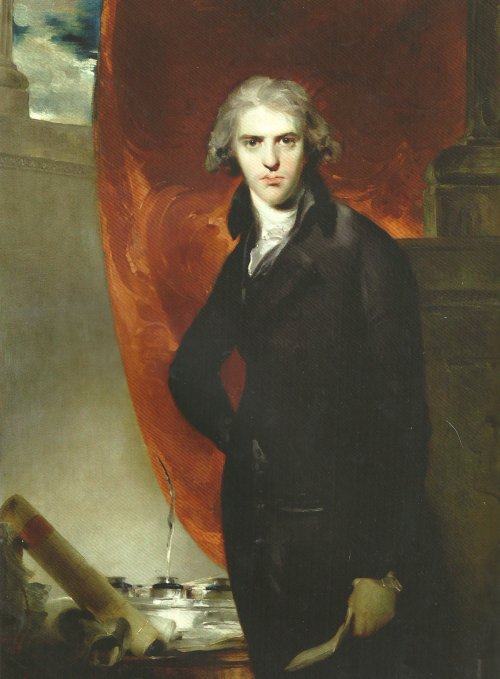

On entering the exhibition you are met with the bright gaze from a young Thomas Lawrence.

Self Portrait, Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1788 Image @PRA

Under the title of the exhibition, “Regency Power & Brilliance,” hangs a self-portrait, of oil on canvas, completed in the years 1787 – 1786 when Lawrence was 19 years of age. It is typical of Lawrence’s style that it is new and innovative for it’s time. Lawrence is sitting with his body facing to the right and his head turned to look at you the viewer over his right shoulder. The stare is steady, confident and penetrating. His face is almost illuminated and glows brightly out of the picture.

Bristol in the 18th century

Thomas Lawrence was the leading portrait artist of the Regency period. Born in 1769 at 6 Redcross Street, Bristol, he came from a humble background. His father was also called Thomas Lawrence and his mother was Lucy Read, the daughter of a clergyman. Thomas’s father had several jobs, including innkeeper at the White Lion in Bristol. Later became the innkeeper of the Black Bear in Devizes where famous writers and artists, including David Garrick the actor and theatre owner, on their way to Bath, would stay. The young Thomas Lawrence would meet them.

The Black Bear in Devices

The Black Bear in Devices

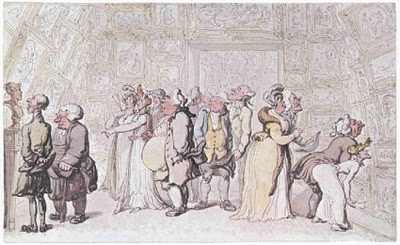

Thomas was the entertainment in the inn. He would recite poetry and use his natural talent for sketching people to amuse and interest them. When the senior Lawrence became bankrupt, the family moved to Bath where the younger Thomas Lawrence took over being the breadwinner for the family by selling his sketches and miniature oval portraits in pastel and chalk. Some of the wealthy people in Bath commissioned his work. From an early age Thomas had had prodigious natural talents for sketching and reciting poetry. Wealthy people allowed him to study their collections of paintings and Lawrence’s drawing of a copy of Raphael’s Transfiguration was awarded a silver gilt palette and a prize of 5 guineas by the Society of Arts in London. In 1787 he moved to London where he was introduced to Joshua Reynolds. He started exhibiting at the Royal Academy exhibitions held at Somerset House and his career took off.

Royal Academy at Somerset House, Viewing Art, Rowlandson

The period in history that Lawrence came to prominence was also to have an affect on his development as an artist. There was much turmoil and political change. There was The French Revolution and the long wars against France. Once these came to an end, Thomas was able to travel across Europe. He did this commissioned by the Prince Regent, later George IV. He was able to make portraits of many of the great names of the time – generals, Emperors and the Pope. On his return from Europe in 1820 he was elected as the president of the Royal Academy and produced some of the best portraits of the time. Unexpectedly he died in January 1830 and was honoured with a state funeral.

What is evident in this exhibition is Lawrence’s original ideas, his naturalism and his particular use of colours.

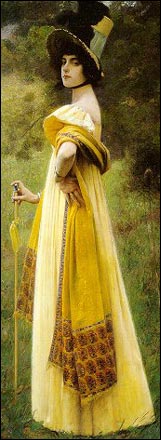

Elizabeth Farrren, Thomas Lawrence. Image @Met Museum

One of his early portraits, when he had only begun his career in London in 1790, was of Elizabeth Farren. He was only 21 at the time and this particular portrait attracted peoples interest. It shows a full length portrait of a slender, beautiful young girl caught in the act of walking through a rural landscape of trees and pathways with her dizzy blond head high in the dramatic surroundings of a stormy sky and dressed in a shimmering three quarter length white silk shawl over a long white gauze like garment. With this portrait and with all the others in the exhibition, for all the costume, dress and surroundings they might have, what always stands out, like an illuminated beacon, is the face of the person in the portrait. This is the most important part. It shows the persons character, and personality. Elizabeth has pale smooth skin, bright red lips and eyes that smile at you the viewer.

Emilia, Lady Cahir, later Countess of Glengall, Thomas Lawrence

What is evident with all the pictures in this exhibition is that when you are standing looking at one of these portraits, no matter how many other people there are in the gallery, it’s just the two of you. You could almost have a conversation together. The paintings certainly allow you to relate to them in a very personal way. I think this is true of all of Thomas’s portraits. Many of the portraits of beautiful young women, as with the Elisabeth Farron portrait, show them, young, always beautiful but often unmarried. The full title to this particular portrait is, Elizabeth Farron, later Countess of Derby. There are a lot of portraits with the name and then the phrase,.. “later the duchess of…” appended to the end. These portraits must have served an important part of the marriage trade. I certainly felt my blood rising at the sight of some of these beauties.

Three Colleagues, Thomas Lawrence

Thomas Lawrence showed great originality. One of his portraits of 1806, of Sir Francis Baring, John Baring, his brother and Charles wall, shows three businessmen contemplating business. It’s extraordinary. They have their work set out in front of them spread on a table and they are planning, scheming, thinking, working things out. It is an action packed picture. Although they are not walking or physically moving anywhere in the picture, things are happening, great decisions are being made right there in front of you. The different angles and poise of each character is quite disconcerting at first. It is not smooth and elegant. It shows action of thought, creativity and influence.

Charles William Vane Stewart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry

Another thing I noticed and it became a quest for me to find in each portrait throughout the exhibition, was Lawrence’s use of the three colours red, white and black. At first I thought, why would he include these in every picture he painted. They do create very dramatic atmospheres. The Elizabeth Farron portrait has bright red lips, masses of white in her dress and one small pitch black shoe poking from under the hem of her dress but many of the other portraits have great swathes of each of these three colours.

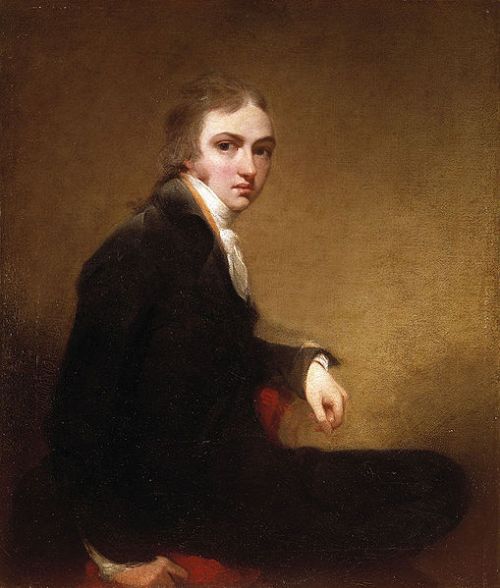

Arthur Atherley, Thomas Lawrence

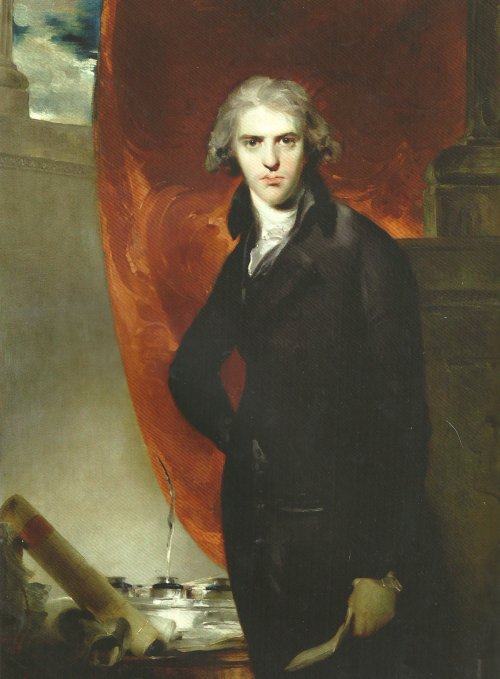

The title of the exhibition is, “Regency Power and Brilliance.” Lawrence paints many of the leading figures of that period from right across Europe. You might think, well how does the power bit enter into portraits of individuals? If you want to see ultimate overarching power embodied in an individual human being you only have to look at the faces in Lawrence’s portraits. All the men show this in their eyes, their demeanour. One small room in the gallery has three portraits of three different men. Arthur Atherley is a youth of about twenty who has just left Eton College, one of the top public schools. He is shown in 1792. The next shows Robert Banks Jenkinson 2nd Earl of Liverpool. This one is painted when the sitter was in his late twenties.

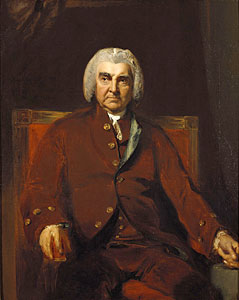

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

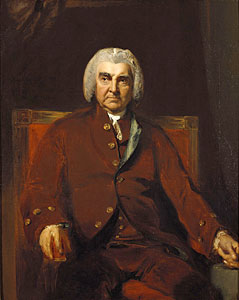

The final picture shows, Edward Thurlow, Baron Thurlow. It was painted in 1802 when he was in his early seventies and he had retired. They are the different stages of a mans life. Arthur Atherley has a precocious energy, a steady stare revealing a sense of utter belief in his powers and where and what he is about to achieve in life. There is no swerving of thought or doubt. He is totally assured of his position and power in life. It’s quite unnerving to see this unwavering belief looking you right in the eye especially from somebody so young. I kept coming back to this portrait. He has long luxurious black hair, a bright red ornate coat and a bright luminous white neckerchief. The three colours work in a very dramatic way in this picture. Robert Banks is a thin spider like creature, slightly twisted and turning his face towards you from the picture, dressed in black from head to foot. A white pale face looking straight at you, looking into your very soul. He looks full of energy. He wants to get things done with his rolls of documents before him. His personality is like a force of nature almost leaping out of the portrait at you. He can get things done. No doubt about that.

Baron Thurlow, Thomas Lawrence

Finally Edward Thurlow, at first looks, benign, very pleasant and friendly and almost smiling but the eyes are piercing and forceful. He is friendly but you couldn’t cross him. He wants talent, imagination, achievement and hard work from anybody who works for him. The three portraits, although of different people, could almost be the same person at different times of their life. In that small room in the gallery it’s quite an encounter. You could almost feel, coming away, that you have been for a tough penetrating job interview.

Master Lambton, Thomas Lawrence

Lawrence’s women fall into various categories. He obviously liked women and children too. There are quite a few pictures showing children. The children are active, playing, interacting, sometimes in a precocious way towards their mother or father in the pictures. He shows real children, not posed children.

Mrs. Jens (Isabella) Wolff, Thomas Lawrence

His friend Isabella Wolf, who may have been his lover, is shown in two portraits. He drew and painted her over many years. The painting of her done in 1803 shows her examining some Michaelangelo prints. She was also separated from her husband. So this picture shows an intellectually curious women who also has broken the bounds of society in her personal life. There are also portraits of Queen Charlotte and Princess Sophia. Royalty is a theme that runs through the exhibition.

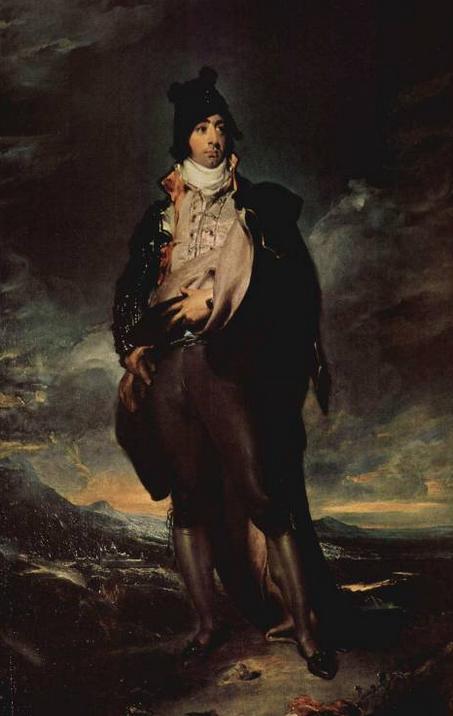

John, Lord Mountstuart, Thomas Lawrence

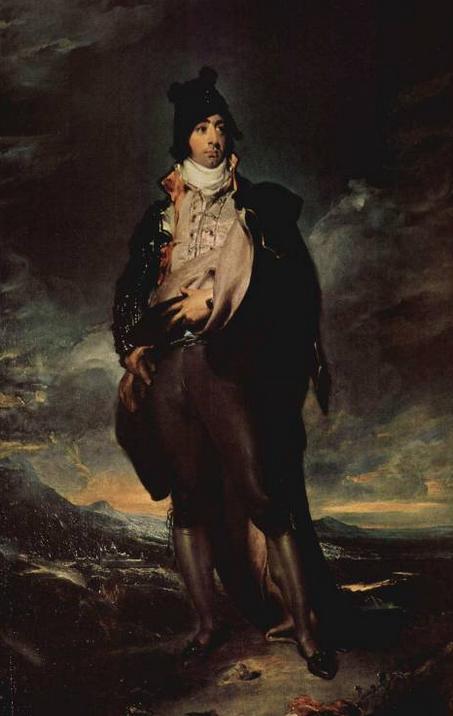

The picture that is most controversial is that of John, Lord Mountstuart.. He was a young politician and had lived in Spain for a while because he was the son of Britain’s ambassador to Spain. Lawrence painted him in 1795 when he had just returned from Spain. In many ways the picture is shocking. It is a full-length, life size portrait. It is hung so that at eye level you are confronted by a pair of very muscular legs showing all the muscular contours sheathed in very tight black leggings. As you look up you are confronted by a rather large black shining bulge in the crotch area. The top half of his body is swathed dramatically in a swirling fur trimmed embroidered black cloak with a dark jowelled, bright eyed, ruddy cheeked quite beautiful face surmounting the whole confection. It is a very erotic picture to say the least. It has lead to questions about Thomas Lawrence’s sexuality. But if you took one of his female portraits, almost any of them, you can say the same thing. Sensuality and a slight erotic air pervade many of Lawrence’s pictures.

George IV when Prince of Wales, Thomas Lawrence

There are fifty-four pictures in this exhibition and each of the people portrayed in them are a delight to be with and a pleasure to spend time with. Some other characters you may care to come across are Arthur Wellesley, The Duke of Wellington, King George IV as King and also as Prince Regent, Field Marshall Blucher, who lead the Prussian forces who pursued Napoleon, Charles, the Archduke of Austria and Pope Pius VII and many more delightful and very interesting people.

- Pope Pius VII, Thomas Lawrence

I have tried to give you a taste and flavour of this exhibition. (Click here to see a PDF document of more paintings in the exhibit.) It is not something you can grade from good to bad, give a level to, say you must see it, or not see it, or apply any subjective or objective assessment like that. What I can say though, if you do get a chance to see it, be prepared to meet real people face to face in those portraits. You will have some very interesting encounters along the way. You will learn something about power, personality, individual characters and yes, brilliance.

Read Full Post »

Dress for Excess: Fashion in Regency England, opened on February 5 and will run for a full year. The cost of the exhibition is free for those who purchase tickets to see the Royal Pavilion & Museums at Brighton.

Dress for Excess: Fashion in Regency England, opened on February 5 and will run for a full year. The cost of the exhibition is free for those who purchase tickets to see the Royal Pavilion & Museums at Brighton.