Inquiring reader: Sit back, relax, and grab a cup of coffee or a glass of wine! This is a long post about foxhunting. (Note: because of the helpful suggestions from equestrian readers, crucial edits have been made.)

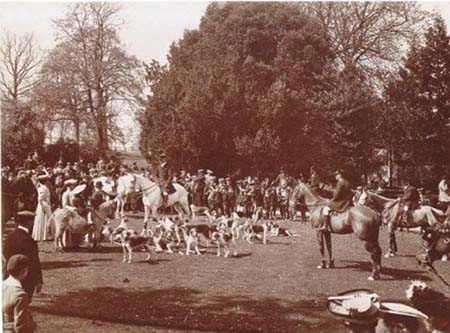

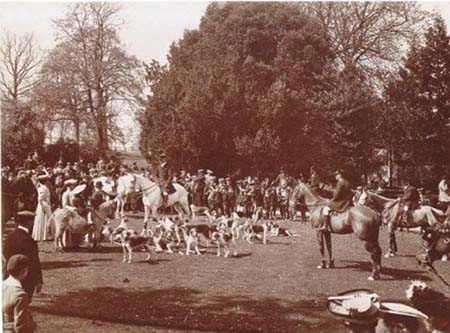

Downton Abbey (Highclere Castle) and the start of the hunt

The fox hunting scenes in PBS Masterpiece Classic’s Downton Abbey fascinated me and prompted me to ask: How accurate was the depiction of this sport? Aside from the fashions, how different was fox hunting in the Edwardian era from the Regency era? And what happened to that wily fox, whose odds of escaping a score of determined hunters and a pack of excited hounds must have been close to zero? Or were they? My research uncovered a few interesting bits of information:

Hounds milling before the hunt. Notice William with refreshments. Downton Abbey

Description of the Hunt:

In 1910, 350 hunts existed in Britain, almost twice as many as today. Foxhunting was one of the few country sports in which women played an active role. It had become so popular that foxes were even imported from Europe to meet demand. The anti-hunt movement was a fledgling organisation concerned largely with horse beating and vivisection. For the vast majority, fox-hunting was seen as a harmless and ancient tradition. – Manor House

Before the start of an Edwardian hunt. Image @The Antique Horse

The Master will sound his horn and he and the hounds will take off on the hunt. Everyone else follows. The hounds are cast or let into coverts, which are rough brush areas of undergrowth where foxes often lay in hiding during the day. Sometimes the huntsmen must move from covert to covert, recasting the hounds until a scent is discovered. Once the hounds pick up the scent of a fox, they give tongue. The hounds will trail and track for as long as possible. Either the fox will go to ground or find an underground den for safety and protection or the hounds will wear him out and overtake him in a kill. Temperature and humidity are huge factors in how well hounds keep the scent of a fox. Often the chase involves extreme speed through brush and growth. A rider will need to be skilled in racing, jumping brooks, logs, brush, and the horses must be in excellent condition as well.” – The history of fox hunting

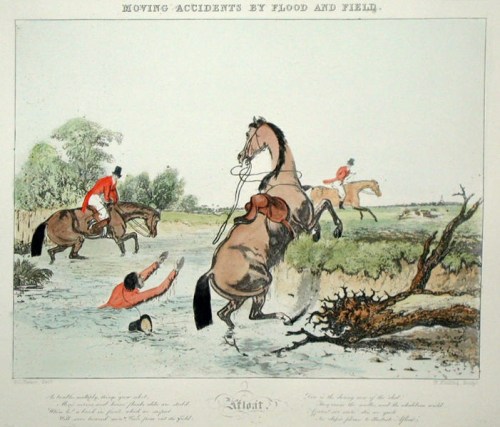

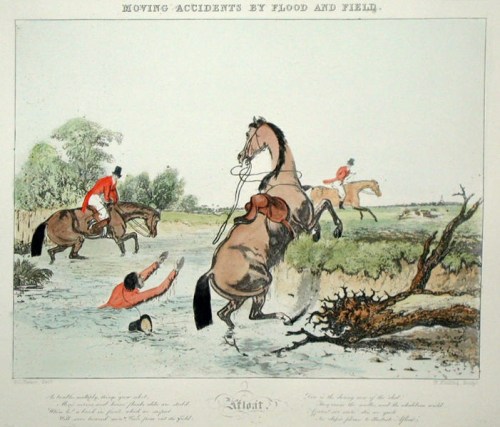

Moving accident by flood and field

Filming the Fox Hunt for Downton Abbey:

While the crew were at the castle they filmed various scenes, inside and out. Lady Carnarvon explained that on one particular day they filmed a hunt. “It was wonderful. It was a beautiful day on the day they were doing it too. The funny thing is the one thing I asked them not to do was go across the lawns because there was to be a wedding. They started very early and they were all hanging around. They were going up and down for hours on end, and then suddenly just out of the laurel bushes went a fox – a real fox. The fox took off towards the secret gardens and the hounds turned in full pursuit. The fox wasn’t caught. It just ran off. The hounds were eventually brought back having gone through a couple of cold frames in the garden. I could see the location manager thinking that is the one thing I asked them not to do,” she laughed. – Highclere Castle is the star of the screen

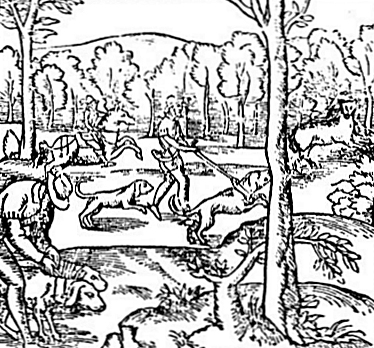

Dirt dog work, circa 1560

History of the Fox Hunt:

Talk of horses, and hounds, and of system of kennel!

Give me Leicestershire nags, and the hounds of old Meynell!

While Hugo Meynell is widely considered to be the father of modern foxhunting as we know it today (his Quorn Hunt between 1753 and 1800 was quite fashionable), hunting foxes with hounds was not new. Evidence exists that fox hunting has been practiced since the 14th century. In 1534 a Norfolk farmer used his dogs to catch a fox, which consisted of hunting on foot and trailing the animal back to its den. Foxes were thought to be “vermin” and left to commoners to hunt. In those early times, royalty and the aristocracy hunted stags, or deer, which required great swathes of open land and an investment in horses, hounds, and stables. Considering the chasing and killing of vermin to be beneath their status, the aristocracy continued to chase stags until these animals became scarce.

Hunting with hounds on foot

Hugo Meynell began breeding hounds that could keep up with the foxes at the same time that an increased number of 18th century men could devote their time to leisurely pursuits. Consequently, the sport of fox hunting began to take off. (See Rowlandson, The Humours of Fox Hunting: The Dinner, 1799 for a depiction of a group of men enjoying the after effects of a hunt.)

There were no formal hunt clubs during this period. Rather, large landowners kept hounds that accompanied them on private hunts. The hunts were not very effective in controlling the number of foxes in any given area, but the sport was safer than the practice of using spring traps, which could snare a human as well as a fox. (Animal traps from the 16th century. )

18th century spring trap

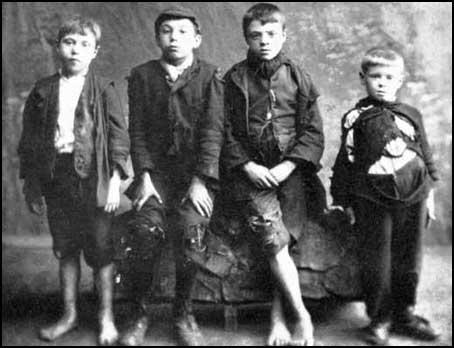

By the early 19th century, a more formal style of foxhunting began to be organized. Roads and railways had cut the land into smaller portions, and it became more convenient for rich landowners and their guests to hunt foxes. Railways also gave a larger number of people in towns and cities easy access to the countryside and an opportunity to join in the sport.

The rising middle clases, eager to improve their social standing, joined the clubs, and by the late 19th century the sport had reached the height of its popularity. In fact, the demand for foxes was so great that some hunts were called off if the probability was high that the fox would get killed. Foxes were so scarce that a large numbers of the animals were imported from Europe to be sold in England.

The Bilsdale Hunt. Image @MSNBC.com

The oldest continuous fox hunt in England is the Bilsdale Hunt in Yorkshire, established by George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham in 1668. Since 2005, foxhunting with hounds has been illegal in Britain, but there are groups that are still unhappy with this turn of events, for foxes are still allowed to be hunted and shot in England. Supporters of the foxhunt state that organized foxhunts never caught enough foxes to affect the total population and that the kills were clean. In addition, foxhunting supports a minor economy of farriers, grooms, horse stables, dog kennels, trainers, veterinarians, shops, inns, taverns, and the like. Since it became organized, the hunt also provided a spectator sport to local villages and market-towns and inspired railroads to expand their services so that participants could join the hunts and travel up and back within a day. The landscape also benefited from the hunt in that landowners planted low bushy coverts for the foxes and maintained their hedges to facilitate jumps. – Encyclopedia of Traditional British Rural Sports: History of Fox Hunting

Foxhunting Schedule:

Fox hunting began on the first Monday of November; traditionally a hunt was held on Boxing Day (Dec 26).

In the early morning workers stopped up the holes of the dens where the foxes rested, forcing these nocturnal animals to find shelter above ground during the day.

Around 11 a.m. the riders (field) would assemble, with around 40-50 hounds.

The Master of the Hounds was in charge of the hunt and supervised the field, hounds, and staff. The huntsman, who had bred the hounds and worked with them, would be in charge of the pack during the hunt.

Chasing the fox. Downton Abbey

Once the group was assembled, the hunstman would lead the pack of hounds and field to where a fox might be hiding. When the fox was flushed out into the open, the group would pursue the fox, with the huntsman leading the group. The field would follow at a gallop and watch the hounds chase down the fox.

When the fox was cornered, the hounds took over.

Hunt festivities included lawn meets, where food and drink were served to the people who gathered together, and hunt balls.The cost of horses, outfits, and operating expenses made the activity prohibitive for those with limited means, and only those with a great deal of money could afford to participate. – What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew, Daniel Pool – p171-173

Women and Foxhunting:

Waiting for the hunt to begin, Downton Abbey

Few women rode in a fox hunt during the Regency period. It took great skill and courage for a woman to join the hunt, for in those days the side-saddle lacked the leaping horn, which offered a more secure seat and made taking fences safer.

The Inconvenience of wigs, Carle Vernet. Image @Yale University Library

By the mid-19th century, women began to join in the sport in greater numbers. An article written by Catriona Parratt discusses women’s involvement:

“Preeminent among these activities was foxhunting, one of the few sports for which there seems to have been no rigidly prescriptive code limiting women’s participation. In fact, some women embraced the sport with a zest which was evidently not considered inappropriate. This may be explained in part by the extreme social exclusivity which attended to the leaders of the foxhunting set. Members of the aristocracy and the upper middle classes were probably sufficiently secure in their status to ignore, to some extent, more bourgeoise notions of respectability… According to one enthusiast, 200 riders was considered a poor turn out, while few meets attracted less than 100 men and women. A figure of thirty women is given in an account of the Tipperary Hunt in the 1902 season, but the overall evidence is very impressionistic…

There are also several accounts of women achieving the honour of being the first to ride in at the death of the fox, something which seems not to have offended their supposedly more delicate sensibilities. In a 1900 meeting of the Dartmoor Pack, the brush [tail] was awarded to a Miss Gladys Bulteel, of whom it was noted that her pony “was piloted with exceptional skill,” while in a previous month’s run of the same pack, a Miss Dorothy Bainbridge claimed the coveted trophy. None of this is to suggest that women participated in equal numbers or on equal terms with men… Rather, it is clear that some women were active, enthusiastic, and skillful participants who were drawn to the sport by “the enjoyment, the wholesomeness, even the nerve-bracing dash of danger.” – Athletic “Womanhood”: Exploring Sources for Female Sport in Victorian and Edwardian England Cartriona M. Parratt*, Lecturer, Dept. of Physical Educ

Kemal Pamuk (Theo James) meets Lady Mary

Comments about the Fox Hunt in Downton Abbey from the Horse and Hounds forum:

As I researched foxhunting, curiosity led me to a discussion forum at the Horse and Hounds website. I wanted to know what the experts thought of the foxhunting scenes in Downton Abbey. Here they are in a nutshell, with the names of the individuals taken off:

Master of the Hunt sounds the call

They should have told that daft lady [Mary] side saddle person to put a bloody thong and lash on her hunting whip and hold it the right way too..thong end up please. Suppose we should be grateful it was’nt filmed in high summer! And WHY film the field and hounds all mingled but apparently in full cry..UUURRRGGGHH it drives me nuts.”

“Not unless they have a leather loop on one end for the thong and lash? Do sidesaddle whips have bone “gate hooks” on the top end?? In one shot the lady did have a thong attached ..but still holding it the wrong way anyway, shortly before, no lash!! Pathetic.”

“My thoughts that the horses were not typical or hunters of that era, also would there have been a coloured, I thought that the craze for colours was a recent thing and they were frowned on in ‘those days’. “

The field follows the Master and pack

I am amazed that finally a TV programme has made the effort to show not only a hunting scene but a lady hunting on PRIMETIME TV and people are moaning about minor details! I hunt side saddle, I do it because I love it, so I was over the moon to finally see something relevant to it on t.v. Would you have preferred they didn’t show it at all and cut the hunting scenes entirely??

Lets not forget these programmes are filmed for public entertainment, they are not historical documentarys. Please could we all be a little more supportive of equines on TV regardless of the reasons, then maybe we would see more.”

“Well if you want to moan about the most minute details of the scenes (and don’t forget, what you see on screen in a STORY not a documentary !!!) why not start with the fact that the forward seat was unknown in Edwardian times?”

Master of the Hunt and pack set off ahead of the field

We noticed the coloured horse too and said no way would they have had one of them!! They only pulled carts in those days. Still – we all got excited when the hunting scene started!!”

Lady Mary and Evelyn Napier

Did anyone spot which hunt’s tail coat was being worn by Mr Evelyn Napier?”

“It was the vine and craven hunt huntsman David Trotman scarlet coat with gold vine leafs on black collar. The Vine & Craven [were] filming at Highclere Castle…”Horse and Hounds forum –

Riding hell bent for leather through the fields. Downton Abbey

Master of the Hunt and other staff:

The Master of the Fox Hounds (MFH) or Joint Master of the Fox Hounds operates the sporting activities of the hunt, maintains the kennels, works with, and sometimes is, the Huntsman. The word of the Master is the final word in the field and in the kennels. The Huntsman is responsible for directing the hounds in the course of the hunt.

The Huntsman usually carries a horn to communicate to the hounds, followers, and whippers-in. Whippers-in are the assistants to the Huntsman. Their main job is to keep the pack all together.” – Human roles in fox hunting

The huntsman drinking a pre-hunt drink. Image @Icons A Portrait of England

From Baily’s magazine of sports and pastimes, Volume 2, 1861, p. 182: “As well might you assert that because a nobleman throws open his house and grounds to the public one or two days in the week from free goodwill that he has not the right to exclude any persons he may object to. A Master of fox hounds hunts his country upon the same conditions. Any landowner can prevent him riding over his fields or drawing his coverts. By the landowners he stands or falls. He recognizes no other power to interfere with his conduct in the field.”

Edgar Lubbock, Master of the Blankney Hunt

Description of the above image: Edgar Lubbock LLB was the Master of the Blankney Hunt at the turn of the 20th century. He was born on 22 February 1847 in St James, London the eighth son of Sir John William and Harriett Lubbock. Educated at Eton and the University of London he studied Law and became an accomplished lawyer. Through his career he held varying positions, including Lieutenant of the City of London, Director of Whitbread Brewery, Director of the Bank of England and in 1907 Lord Lieutenant of Lincolnshire. He died in London on 9 September 1907 aged 60 whilst Master of the Blankney Hunt. – Metheringham Area Mews

The Dogs:

The true point of riding to hounds was (and is) to watch the hounds work. Those who galloped wildly or jumped unnecessarily were termed “larkers” – an insult – and disdained by the serious hunters. – Word wenches, fox hunt

The hounds are the most vocal component of the hunt and the means by which the fox is flushed out and then chased until it was too exhausted to go farther. In England, there were two breeds of dogs that were necessary to the hunt: Harriers, which are slightly smaller than foxhounds, and who chased the fox over hill and dale; and terriers, who followed the fox into the den and dug it out.

Harriers (Hare Hounds or Heirer)

The Harrier, also known as the Hare Hound or the Heirer, is a hardy hound, with a strong nose, that was developed in England to hunt hare. Hare hunting has always been popular in England, sometimes being even more popular than fox hunting because hunters could trail their hare hounds on foot, without the need for the many horses required to follow fox hounds on the hunt. Moreover, hare hunting was never reserved to royalty; it was always accessible to commoners, who could add their few Harriers to a “scratch pack” made up of hounds owned by different people and still participate in the sport. Reportedly, in 1825, the slow-moving Harrier – in size between the larger English Foxhound and the smaller Beagle – was crossed with Foxhounds to improve its speed and enable it to better hunt fox in addition to hare. – Harrier overview

Terriers

Fox Terrier. Image @Chest of Books

With the growth of popularity of fox-hunting in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries, terriers were extensively bred to follow the red fox, and also the Eurasian badger, into its underground burrow, referred to as “terrier work” and “going to ground”.[1] The purpose of the terrier is that it locate the quarry, and either bark and bolt it free or to a net, or trap or hold it so that it can be dug down to and killed or captured.[2] Working terriers can be no wider than the animal they hunt (chest circumference or “span” less than 35 cm/14in), in order to fit into the burrows and still have room to maneuver.[3] As a result, the terriers often weigh considerably less than the fox (10 kg/22 lbs)[4] and badger (12 kg/26 lbs),[5] making these animals formidable quarry for the smaller dog. – Wikipedia

My terrier no longer has the slender girth to chase a fox into its den, for he eats too many doggie biscuits.

Read more about terriers:

The Kill:

Foxes were killed in one of two ways:

1) Hounds chased the foxes until they were caught and then dispatched it. There seems to be a widespread disagreement about the kill, some saying it was quick, and that the fox died from a nip to the back of the neck, and others saying that the fox was repeatedly bitten or torn apart, and sometimes died slowly from its injuries.

2) The fox went to ground (inside a hole or den), and then was dug out with terriers.

Animal rights experts also found the chase itself, with the fox hunted to the point of exhaustion, cruel.

I could not show an image of a kill, so I’ve presented you with the opposite image: This young lurcher has adopted a fox cub. Jack, the hound, and Copper, the cub, are famous in the U.K. for their playful wrestling matches. Image @Animal Tourism.com

Final Words about Foxhunting in America:

Since Cora (the Countess of Grantham) in Downton Abbey was an American heiress, the information below regarding the American fox hunt is appropriate to this post:

Description of a Fox Hunt by a New England minister

Fox hiding in the covert.

Foxhunts were imported into America in the 17th century. In 1799, a wry New England minister gave a glimpse of the sport in the New World: “From about the first of Octor. this amusement begins, and continues till March or April. A party of 10, and to 20, or 30, with double the number of hounds, begins early in the morning, they are all well mounted. They pass thro’ groves, Leap fences, cross fields, and steadily pursue, in full chase wherever the hounds lead. At length the fox either buroughs out of their way, or they take him. If they happen to be near, when the hounds seize him, they take him alive, and put him into a bag and keep him for a chase the next day. They then retire in triumph, having obtained a conquest to a place where an Elegant supper is prepared. After feasting themselves, and feeding their prisoner, they retire to their own houses. The next morning they all meet at a place appointed, to give their prisoner another chance for his life. They confine their hounds, and let him out of the bag—away goes Reynard at liberty—after he has escaped half a mile—hounds and all are again in full pursuit, nor will they slack their course thro’ the day, unless he is taken. This exercise they pursue day after day, for months together. This diversion is attended by old men, as well as young—but chiefly by married people. I have seen old men, whose heads were white with age, as eager in the chase as a boy of 16. It is perfectly bewitching. The hounds indeed make delightful musick—when they happen to pass near fields, where horses are in pasture, upon hearing the hounds, they immediately begin to caper, Leap the fence and pursue the Chase—frequent instances have occurred, where in leaping the fence, or passing over gullies, or in the woods, the rider has been thrown from his horse, and his brains dashed out, or otherwise killed suddenly. This however never stops the chase—one or two are left to take care of the dead body, and the others pursue.” – Colonial Williamsburg, Personable Pooches

Middleburg Christmas parade. Image @Washington Post

Comment made on a Word Wenches post by a reader who lives in Virginia’s hunt cup country: I live in Virginia hunt country, in fact in the Old Dominion hunt area. My property deed has one covenant on it. We must allow the huntmaster through. We can deny the rest of the hunt if we want. The covenant was signed by King Charles (I am not sure which one). Fauquier County has 3 hunts and the U.S. largest Steeplechase race, the Gold Cup. .. Many of the more recent mansions (post US Civil War through the 1920s) in Fauquier and neighboring Loudoun were built as hunt houses. – Word Wenches, Fox Hunting

Jacqueline Kennedy. Equestrian outfit in the 1970s.

Etiquette and Dress Code of a Fox Hunt:

The etiquette of the hunt field was (and is) as intricate and strict as that of the ballroom. I imagine (and please correct me if I am wrong), that each club has its own variation of rules. Loudoun County is west of Washington D.C. and sits near the middle of the hunt country of Northern Virginia, where Jacqueline Kennedy frequently hunted when she lived in Georgetown. Click here to read the extensive rules of etiquette of the Loudoun Hunt: Etiquette and the rules of Attire.

Edwardian riding habit. Image @side saddle girl

More on the foxhunt:

Addendum to original post:

This post began innocently enough, for I had no idea about the emotions surrounding the fox ban. Various views are presented in the comment section. Tony Grant, who writes for this blog and who lives in London, said in an email:

A fox creeps in Tony's yard towards the dustbins

Because foxes are no longer hunted their population has expanded unbelievably. They no longer keep to the countryside but live in the towns and cities as scavengers. They live in dens created in parks and the bottom of peoples gardens. They scavenge dustbins. We have an epidemic where I live in South London. They walk down my road and enter my garden on a regular basis. They are not afraid of humans.

Here are some pictures taken in my back garden. This fox wanted to raid our dustbins.

Read Full Post »