Growing Older with Jane Austen by Maggie Lane: Review and Highlights by Brenda S. Cox

“Me! a poor, helpless, forlorn widow, unfit for anything, my spirits quite broke down . . .”—Mrs. Norris, Mansfield Park, chapter 3

“That Lady Russell, of steady age and character, and extremely well provided for, should have no thought of a second marriage, needs no apology to the public, which is rather apt to be unreasonably discontented when a woman does marry again, than when she does not; but Sir Walter’s continuing in singleness requires explanation.”—Persuasion, chapter 1

Last month we began looking at older characters in Jane Austen’s novels, drawing from Maggie Lane’s fascinating book, Growing Older with Jane Austen. We saw the importance of beauty in making matches, and the position of women as wives and mothers, or as single “old maids.”

Next, Lane turns to older men, in the chapter:

Still a Very Fine Man (chapter 6)

With the exception of Sir Walter Elliot, the older men in Austen are less concerned about their appearances. But they are more likely to want to remarry than the older women. This is because men generally contribute financially to the marriage. If women are lucky, money may pass into their hands when they are widowed and they can be independent.

For the men, though, they depend on women for housekeeping, and they are uncomfortable without a female relative caring for them and their households. Younger men like Henry Tilney or Colonel Brandon, expecting to marry, may be happy with a paid housekeeper for the time being. But older men like the Dashwoods’ great-uncle want a female relative to care for them. So those young enough to remarry, like Mr. Weston and Mr. Dashwood (Elinor’s father), are likely to find a second wife, and in Austen’s novels they find happiness.

Sir Walter Elliot wanted to remarry, but failed. He probably proposed to women much younger than himself, with his eye for beauty. They were not interested in a “foolish, spendthrift baronet.” Instead, he depends on his daughter Elizabeth, who is very much like himself. Unfortunately she does not balance him, “promot[ing] his real respectability,” as his wife had.

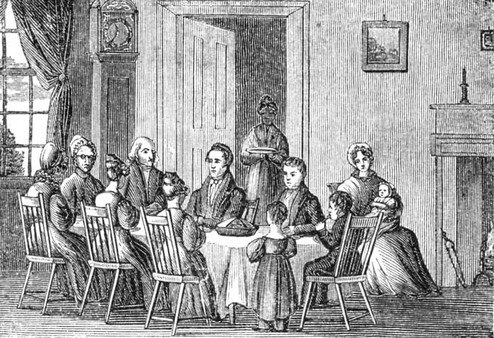

C.E. Brock, public domain

Mr. Woodhouse, of course, also depends on his daughter Emma, and she carefully fulfills her duty to him. He is at least loving, though selfish. In contrast, General Tilney bosses his daughter around harshly and keeps control of his household in his own hands.

Austen presents some happy marriages of older men. “Older men have usually settled down to an accommodation with their wives, and Austen presents many portraits of ageing couples who seem well-knit together: the Shirleys, the senior Musgroves, and the Morlands, for example” (Lane, 109). Even Sir Thomas Bertram and Mr. Allen are always courteous to their rather foolish wives.

Merry Widows (chapter 7)

The next three chapters explore the varying possibilities for widows. Lane says, “The conventional ‘merry widow’ of literature is an unprincipled predator with a voracious sexual appetite and a carefree disregard of conventional morals” (122). The only widow like that in Austen is, of course, Lady Susan Vernon (of Lady Susan), whom Lane discusses at length.

Another widow in Austen who follows a different contemporary stereotype is Mrs. Turner of The Watsons. She is taken in by a fortune-hunting Irish officer; she marries him and leaves her niece penniless.

Other widows in Austen’s novels, like Mrs. Jennings and Lady Russell, have a comfortable income and seem content to remain unmarried. Austen makes an interesting remark about double standards when she says of Lady Russell that “the public . . . is rather apt to be unreasonably discontented when a woman does marry again, than when she does not.” Lane explains that if a woman doesn’t need to remarry for money or a home (as Lady Susan does), she is “giving proof of continuing sexual desires.” A man, though, was expected to have continuing sexual desires, and “if he lost one wife, he was thought to be doing a good thing in seeking another—and in giving another single woman the chance to be wed” (Lane, 132).

In her letters, though, Austen commended a woman, Lady Sondes, who was being criticized for marrying again (and apparently had not married for love the first time). Jane writes, “I consider everybody as having a right to marry once in their Lives for Love, if they can” (Letters, Dec. 27, 1808).

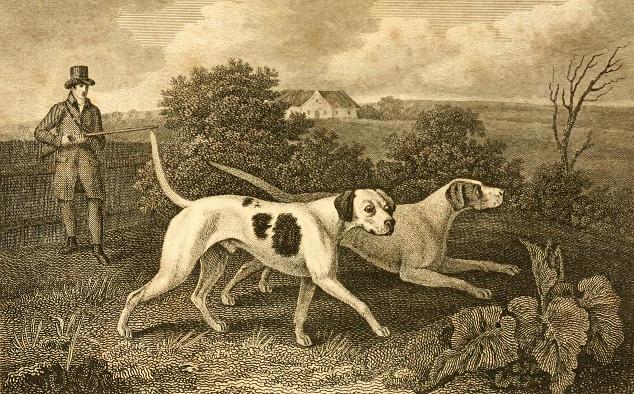

C. E. Brock, public domain

Four Dowager Despots (chapter 8)

Not all of Jane Austen’s widows are as loving as Mrs. Jennings and Lady Russell. While power was usually held by men in Austen’s world, Austen gives us four rich widows who tyrannize others. (Think for a minute; who are they?) Mrs. Ferrars of S&S, Lady Catherine de Bourgh of P&P, Lady Denham of Sanditon, and Mrs. Norris of Mansfield Park. (Mrs. Norris doesn’t have a lot of her own money, but exercises authority on behalf of her “supine sister and absent brother-in-law.”)

Lane writes, “Only Lady Denham is a true dowager, the strict definition of which is a woman whose income derives by legal pre-arrangement from her late husband’s estate, the estate [and title, if there is one] having passed on his death to his heir” (136). Lady Catherine and Mrs. Ferrars appear to completely control their late husbands’ fortunes. But all of them show “a mixture of self-importance and interference in others’ lives” (Lane, 137). Lady Catherine, in particular, controls her whole parish, and it appears that Lady Denham also has great influence in Sanditon.

Lane contrasts two older women in Sense and Sensibility: the manipulative Mrs. Ferrars, who uses money to control her sons, and Mrs. Smith, who controls Willoughby financially. “The telling difference between Mrs. Ferrars and Mrs. Smith is that the latter only wants her young relation to be good, not rich or distinguished” (Lane, 142). Mrs. Smith was likely an elderly maiden lady, of “uncompromising propriety,” who was given the honorary title of “Mrs.” Her motivations are better than Mrs. Ferrars’s selfishness.

Not the Only Widow in Bath (chapter 9)

Another dowager, Mrs. Rushworth, is not a despot as far as we know. When her son marries, she retires, “with true dowager propriety,” to Bath, ready to boast of Sotherton during her evening parties. While Mrs. Elton tries to convince Emma to go to Bath to find a husband, many older people went for other reasons. People like Austen’s parents moved to Bath for “freedom from the cares of a country property and housekeeping; company on tap; and easy access to medical attention as well as to shops, libraries, concerts, and plays” (Lane, 157). (Sounds good to me; I wish I could afford to retire to Bath!)

No longer a place of high fashion, Bath now appealed to “the kind of people Jane Austen knew and wrote about: the minor gentry with a taste for social life and the means to indulge their real or imagined illnesses; the less well-off, especially single women, desperately clinging to their shreds of gentility in a place where living was comparatively cheap; well-funded widows and retired professional men with their families . . . and . . . a motley assortment of hangers-on and would-be social climbers” (Lane, 157-8).

Sir Walter Elliot, a widower, goes there to “be important at comparatively little expense.” Lady Russell, a widow, spends every winter there, “finding mental refreshment in meeting up with old friends and getting all the new publications.” Widowed Mrs. Thorpe of Northanger Abbey goes to find husbands for her daughters. Impoverished invalids like Mrs. Smith of Persuasion go for medical care, while a similar widow, Mrs. Clay, is looking to marry again.

Because of changes in Bath, in Austen’s later novels, “Bath appears not as the place of fun and frivolity it is in Northanger Abbey, but increasingly the choice of the old and dreary. . . . Austen’s Bath is not without its young people but it is an appropriate stage for so many of her older ones” (Lane, 170).

Age and Money (chapter 10)

How they live in Bath or elsewhere depends on their income. Some of Austen’s characters got richer as they aged. These include Mr. Weston, Mr. Cole, John Knightley, Robert Martin, Mr. Jennings (now deceased), Mr. Gardiner, Captain Wentworth, and Charles Bingley’s father. They all prospered in their work.

Others, though, like Austen’s naval brothers and Henry, got poorer as they aged. They suffered reverses from “the vagaries of their profession[s].” Captain Harville has been wounded, causing him to fall on hard times, and Mrs. Smith of Persuasion has lost a fortune due to her husband’s extravagance. Mrs. Bates, a clergyman’s widow, lost her income when her husband died.

Those in the lower classes might be miserable in old age, like “old John Abdy” of Emma. Well-off families, though, were expected to care for their household servants in old age. For example, three servants of Edward Ferrars’s father receive yearly annuities from his estate.

Wills and inheritance, of course, played an important part in Austen’s novels and her life. Most famously, the entail on the Bennets’ estate, and the Dashwoods’ uncle’s will, cause the girls in the story to be urgently in need of husbands.

The Dangerous Indulgence of Illness (chapter 11)

Mrs. Bennet is constantly fearing her husband’s death, which will leave the family penniless. Illness and death were constant threats in Austen’s world (as they are today, of course). This chapter discusses Austen’s final illness. Surprisingly, she wrote Sanditon during that time, which includes absurd hypochondriacs exaggerating their own illnesses.

Sea-bathing was considered a cure-all, and the Knightleys, Dr. Shirley, and Mary Musgrove try it at seaside resorts like the fictional Sanditon. Others go to Bath to take the waters for their “gout and decrepitude.” Mr. Allen, General Tilney, Admiral Croft, and Mrs. Smith of Persuasion go to Bath for their health, as did some of Austen’s friends and relations.

C. E. Brock, public domain

Illness is also a way to control others in Austen’s novels. Dr. Grant, Mary Musgrove, Fanny Dashwood, Mrs. Bennet, Mr. Woodhouse, and Mrs. Churchill all use illness or pretended illness to get their own way.

Once Mrs. Churchill actually dies, though, her illnesses are taken seriously. Austen uses several deaths as plot devices, including this one which frees Frank to marry. Dr. Grant’s death similarly frees Edmund and Fanny to take the living of Mansfield Park.

Lane says, “Mansfield Park is the only novel in which ideas of the hereafter find a place” (206). Fanny worries about Tom, during his illness, considering “how little useful, how little self-denying his life had (apparently) been”—she’s worried about him not going to heaven. And Austen indicates that, while society does not punish a man for adultery as it does a woman, the penalties “hereafter” will be more equal.

The chapter includes a fascinating list of the funeral expenses for Elizabeth Austen’s elaborate burial (Edward Austen Knight’s wife). For example, 22 mourning cloaks were hired for the day, and 60 pairs of black gloves bought for family, servants, and others, including the carpenter and bricklayer.

“Jane Austen’s attitude to the death of others ranged between the insouciant, the pragmatic, and the heartfelt” (Lane, 216). She of course approached her own death very seriously. She took Holy Communion one last time, while she could still understand it, about a month before her death.

For more on this topic, see my article, “Preparation for Death and Second Chances in Austen’s Novels,” which draws partly from Lane’s ideas.

Conclusion

The author explores how Austen might have fared in old age. She would probably have become more famous. Her sister Cassandra, Jane’s heir, prospered financially as the years went on, and Jane would have prospered with her.

The book ends, “Apart from the sad loss of Jane, Cassandra’s old age was in fact a secure and comfortable one. If only she had been able to share it with her sister” (Lane, 225).

I’ve only been able to give you a small taste of the riches in Growing Older with Jane Austen, but I hope you’ve found some ideas you can pursue on your own. If you can get a copy of the book (perhaps through your library), I highly recommend it. It’s well worth exploring the lives of older men and women in Austen’s novels and in Jane Austen’s world.

What do you think would have been most difficult about growing older in Jane Austen’s England? What might have been better about it than growing older in our society today?

For more on the topic of aging women in Jane Austen’s novels, see:

“Growing Older with Jane Austen, Part 1”

“’My Poor Nerves’: Women of a Certain Age on the Page,” about perimenopausal women in Austen

“Past the Bloom: Aging and Beauty in the Novels of Jane Austen,” by Stephanie M. Eddleman, a fascinating article

“Three Stages of Aging with Pride and Prejudice,” by Emily Willingham, a light look at how we identify with different characters as we have more life experience

“Age and Money in Austenland”: Susan Allen Ford’s review of Growing Older with Jane Austen

And, of course, the source for most of these two posts:

Growing Older with Jane Austen, by Maggie Lane

Brenda S. Cox writes about Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen. Her recent book is Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England.

This June she will be speaking about Mr. Collins at Jane Austen Regency Week in Alton, England, and would love to see some of you there!

![brock-na3 [ Brock, Northanger Abbey (Molland’s)]](https://i0.wp.com/janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/brock-na3.jpg?w=246&h=393&ssl=1)